|

||||

|

|

|||

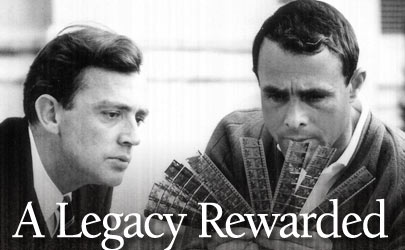

| Richard H. Kline, ASC is honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award for a diverse career of impressive imagery. |

|

|||

“There are so many great faces up on those walls, so much history,” says director of photography Richard H. Kline, ASC, gazing wistfully at a display of black-and-white portraits depicting past and present members of the American Society of Cinematographers. Pondering this “wall of fame” at the organization’s Hollywood Clubhouse, he points out images of Burnett Guffey, James Wong Howe, Philip Lathrop and other exceptional talents. “I was very lucky to have worked with them and so many others as an assistant and operator. While they probably didn’t know it, they were my teachers, my mentors. I never had any formal training as a cinematographer, but I learned so much from just being in their presence.” Kline assisted and operated on more than 200 motion pictures before becoming a director of photography in 1963, after which he compiled 46 feature credits. He is a product of the Hollywood studio-system heyday of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, an invaluable link to a time when filmmakers could focus almost exclusively on practicing their craft and improving with each picture. As a cinematographer, Kline earned Academy Award nominations for the lavish 1968 musical Camelot and the 1976 remake of the epic King Kong. His other credits include Hang ’em High, The Boston Strangler, The Andromeda Strain, The Mechanic, Soylent Green, Battle for the Planet of the Apes, Mr. Majestyk, The Fury, Who’ll Stop the Rain, Star Trek — The Motion Picture, Breathless, Body Heat, All of Me and The Competition. Standing in the ASC Clubhouse, Kline points to a portrait of pioneering cameraman Philip Rosen, who co-founded the ASC in 1919 and became its first president. “He was my uncle, you know,” he says with pride. “I’m actually the fourth member of my family to be a part of the ASC. My father, Benjamin, was a member, and my other uncle, Sol Halperin, was also a president. I guess you could say I was genetically predestined to become a cameraman.” Given Kline’s dedication to his craft and commensurate success, he seemed equally destined to be honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award, which is presented annually to an individual who has made exceptional and enduring contributions to the art of filmmaking. He will receive the award during the 20th annual ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards on February 26. Kline notes that his first memory of being on a film set was at the age of 7. His father’s long career behind the camera comprised more than 350 credits, many of them eight-day-wonder Westerns for the likes of Charlie “The Durango Kid” Starrett, Tex Ritter and Buck Jones. Asked if he was inspired to follow in his father’s footsteps at a young age, Kline replies, “Not in the way you might think. He was away from home working on location quite a bit while I was growing up, and I had different interests. I was much more interested in surfing, which I’ve done all my life. But after I graduated from high school in 1943, my father got me into the camera department at Columbia Pictures.” With World War II raging, the elder Kline reasoned that the experience could qualify his son to work on a camera unit when he entered the service. The 16-year-old lad started out as a slate boy for Rudolph Maté, ASC on Cover Girl, which showcased Rita Hayworth and Gene Kelly in elaborate dance routines. “I quickly learned what great technicians we had on the set,” says Kline. “It was a different time back then. We didn’t have crab dollies, handheld cameras or the sophisticated lighting units and grip equipment that we have today, but we learned efficiency. And our directors were extremely efficient specialists who could get 100 setups a day. There was no wasted time, and there was often a card game happening under the tripod between shots!” Kline quickly advanced to first assistant cameraman and worked on other films before he entered the U.S. Navy in 1944. He was stationed at the Photo Science Laboratory in Washington, D.C., before shipping out to the Pacific theater, where he stayed until mid-1946. After returning to the States, he began working as an assistant at Columbia on every genre of film and with an array of directors and cinematographers. His first assignment upon his return became one of his most memorable: assisting Charles Lawton Jr., ASC during the shooting of Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai. “We were on location down in Acapulco and it was a very wild time,” he recounts. “Errol Flynn lent his yacht to Orson for the film, and since Errol wasn’t working at the time, he served as the skipper. Welles was brilliant, and here I was, this kid along for the ride.” Like his father, Kline worked on a lot of Westerns. “We shot many of them just outside of L.A., around Chatsworth and what is now Forest Lawn Cemetery. Our exterior work was all lit with reflectors on some scaffolding; we didn’t have generators or lights. We’d constantly recycle locations, and we knew the area so well that we could coordinate the shoot to take best advantage of the daylight. For instance, there was what we called ‘Panic Peak,’ a bluff that was high enough that we could get in an extra hour of shooting before the sun went down. We never used natural sets; interiors were all done in the studio. “We were constantly working. When your picture finished, you were moved on to another. Between features, I often worked on shorts for the Three Stooges. They were terrific fellows. Jules White was the main director, and what was really funny was his seriousness as a director — one would think he was directing Shakespeare.” Among Kline’s many on-set mentors was Burnett Guffey. “I first worked with him at Columbia, when he was an operator, starting with Cover Girl, and we worked together for many years after he became a cinematographer. He had a formula to his lighting that I learned to duplicate exactly — I learned to duplicate the lighting of most of the cinematographers I worked with, though I could never quite figure out Jimmy Wong Howe. He was more instinctive, whereas Burnie knew what he wanted from the beginning. But I developed my own approach that was a combination of those two [philosophies]. It was instinctive — based on the needs of the story and the scene — but there were things I would naturally start out with. For instance, in lighting a particular room, I’d always start with the windows as my source and then marry the rest [of my approach] to them. You have to start with the basics and then see where they lead.” |

|

|||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|