MATRIX • page 2 • page 3 SUNRISE • page 2 • Q & A |

|

Page 2 |

||

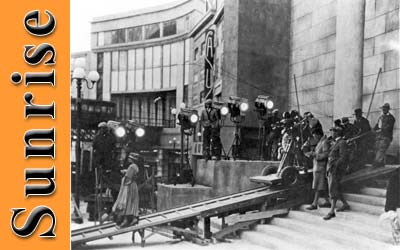

The compositions give an interesting impression of three dimensions. This was achieved by having objects or people in the foreground and action in the background, as in the scene where the city woman is watching the searchers coming back from the rescue attempt. In the interiors, there are lamps in one part of the frame or, in some instances, statues in the foreground. The foreground objects are cut off by the frame on one side, leaving the rest of the foreground open for the main action, enhancing the impression of depth and perspective. This idea of depth had a great influence on Orson Welles; the transmission, apparently, went indirectly through John Ford. Ford liked Sunrise very much, and that's why he put so much depth in How Green Was My Valley and all the other movies he made during that period of his work. Of course, by the times of John Ford and [ASC members] Gregg Toland and Arthur Miller, wide-angle lenses were available, making it possible to more easily obtain that feeling of depth that previously could be gained only through set designing. Some of the other techniques in this movie that influenced cinema later on were slow motion, flashback (in the scene of the drowning), cross-cutting and back projection. (The backgrounds are always important in Murnau's movies; there's always been movement there, as in that scene of Janet Gaynor and George O'Brien in a restaurant with people dancing in the background.) In Sunrise there are often two actions going on at the same time. In the dream sequence, when the man and wife are walking in the city, suddenly they seem to be in the country, then they come back to themselves because there is a traffic jam, and they again are in the city. This is how it was done: they were walking on a roller (conveyor belt) and behind them was a projected film which included the dissolve from the city to the country, and back to the city. On the other hand, when Gaynor and O'Brien are on the tramway, the opposite was done: we see the actual background. This technique was virtually abandoned until the New Wave era; one must wait until Godard to see real moving backgrounds shot from a car, because for years they were all done in the studio. This was because of sound recording and the massiveness of the cameras. This brings up another subject: the mobility of the camera in Sunrise. Silent cinema reach its peak with this movie and others made in the last years before sound came in, from 1925 to 1929. Silent films had become extremely sophisticated. They were perfection itself, especially in the area of camera movements. The camera was very free then, and this film is one of the best examples. When sound came, because of the huge blimping necessary to blot out the noise of the camera mechanism, the camera became very static and the techniques became stiff and studio-like. So it is a pleasure to see that ride on the tramway and note that the sunlight hits according to the movement; if the train turns, the sunlight shifts as well. The sense of reality in that scene is wonderful. Another technique used for atmospheric effect was smoke. Smoke nowadays is very much in fashion, as in E.T. and my own Days of Heaven. Everybody is using smoke or fog. As you can see, that is hardly new, either. Remember the swamp scene where you see lots of smoke? And in the marriage scenes, the smoke materializes the light rays coming in from a high church window to create a divine, holy scene. There are many dolly shots in Sunrise. Some are very well done. I don't think you could make that very first one better today. Rosher and Struss invented the suspended camera dolly over the heads of the players. Apparently, they put tracks on rails on the ceiling (instead of on the floor), as in the scenes in the restaurant. When I first saw Sunrise, I thought they had used a crane dolly, but after reading some articles in old film magazines I learned that it was in fact a suspended camera on a track in the ceiling of the studio. Backlighting was a typical technique of the time, perhaps more so in this movie than in other silent films. There was a constant use of backlighting that practically designed people and made the smoke materialize when the city woman smoked cigarettes. It was so atmospheric you could almost touch the air and smell it. Sunrise is a dialectical movie. It obviously was designed by placing things in opposition. The city woman is in black, she's a brunette, and her clothing shines like a snake's skin. The peasant woman is pale and blonde and dresses in light, soft tones. Purity against evil. The territory of the bad woman is the swamps and the river. She acts by moonlight, whereas the good woman acts in sunlight and has farmland, domestic animals and flowers around her. Another major opposition is that of the country vs. the city. In fact, the shooting script was written in a way so that every scene would be repeated in a symmetrical way - symmetrical but opposite. For example, the first ride on the tramway would be unhappy, the second would be happy. In everything you'll find a counterpart. Page

2

|

||