|

||||

|

|

|||

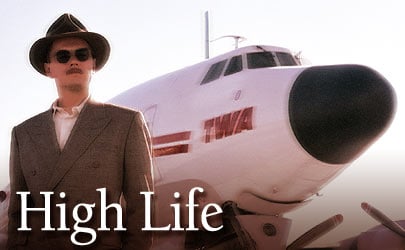

| Robert Richardson, ASC exploits modern methods to craft a classic look for The Aviator, an epic that details the ambitions that drove Howard Hughes. |

|

|||

When Robert Richardson, ASC commits to a project, he does so with a vengeance — as anyone who’s worked with him knows. But one still has to wonder what went through Martin Scorsese’s mind two years ago, when he arrived at a Beverly Hills hotel to discuss his Howard Hughes biopic The Aviator with the cinematographer. The hotel had served as Hughes’s de facto residence during the latter years of his life, and the hunched wraith who greeted Scorsese must have had him wondering if he’d somehow tripped back in time: Richardson had wrapped himself in a terrycloth bathrobe so that only a shock of stringy, shoulder-length, white hair was visible, and he shuffled barefoot from the shadows with toilet paper stuffed between his toes. “I wanted to suggest that I would audition for the role,” Richardson deadpans. “I promised Marty I would lose 30 pounds.” Alas, ’twas not to be, for The Aviator focuses mainly on Hughes’s high-flying salad days in Hollywood, rather than his dementia-plagued twilight years. Richardson believes this tack is what makes the picture interesting: “This story is one the industry has been trying to tell for years. In some ways, I wish it were a longer tale; Marty’s version just hints at some of the early events in Hughes’s life that led to the collapse of his mind. You begin to recognize an obsession with his work, with his women. It wasn’t just one event that took him to that point, it was a series of events, an additive process.” The Aviator is Richardson and Scorsese’s third collaboration, following Casino (see AC Nov. ’95) and Bringing Out the Dead (AC Nov. ’99). The film boasts an ambitious fusion of period lighting techniques, extensive effects sequences and a digital re-creation of two extinct cinema color processes: two-color and three-strip Technicolor. The patented processes utilized a combination of filtration and dyeing to create colored release prints from a matrix of two or three strips of black-and-white negative. Tech-nicolor’s handiwork graced many of the pictures Hollywood released during Hughes’s mercurial career, and Scorsese wanted these unique color signatures to be part of The Aviator’s design. To create a period Technicolor palette that could be applied consistently and quickly to entire scenes or reels, Richardson worked with visual-effects supervisor (and second-unit director) Rob Legato and Technicolor Digital Intermediates (TDI) senior colorist Stephen Nakamura. Their goal was to take the digital intermediate (DI) to a new level of sophistication via 3-D look-up tables, or LUTs. Designed by Josh Pines, vice president of imaging research and development at TDI, the LUT — a dedicated, high-powered graphics processor that could be slipped into the projector during digital color-correction — acted like a digital filter, applying a two-color or three-color look in real time to Cineon scans of The Aviator’s camera negative. Of course, the filmmakers’ visual ambition was hardly confined to postproduction. As usual, Richardson used an array of film emulsions to create and control visual texture on the day. Working in 3-perf Super 35mm (2.35:1) and using Panaflex Platinum cameras and Primo lenses, he shot The Aviator on six Kodak stocks: Vision 500T 5279, Vision 320T 5277, Vision 200T 5274, Vision2 500T 5218, EXR 100T 5248 and EXR 200T 5293. Much like Hughes, Richardson had no compunctions about risking life and limb in pursuit of his passion. While filming a scene in which Hughes (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) crashes his experimental XF-11 plane in Beverly Hills and gets severely burned, Richardson felt stunt flames “completely engulf” his perch on a 30' camera crane. “Even though I had full fireproof attire on, it was hot enough to singe my eyebrows,” he recalls. “Sadly, the laces on my vintage Converse sneakers were burned completely.” AC caught up with Richardson and Legato in New York, when they were in the midst of the DI, to get more details about the production and its unusual post phase. American Cinematographer: The Aviator takes place during the golden years of classical Hollywood cinema. Did you seek to mimic any of the compositional conventions of that period? Robert Richardson, ASC: We did tend a bit toward centered framing, but aside from that we used a very contemporary pattern of coverage. Many of the early three-strip Technicolor films were hindered by extraordinarily bulky cameras, particularly if one included the sound blimp. After viewing Becky Sharp, The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Wizard of Oz, one can only marvel at the minds of men like [ASC members] Lee Garmes, Ernest Haller, Charles Lang, Sol Polito and Ray Rennahan. On The Aviator, we did not attempt to re-create the choreography of period-style camera moves. For a short time, we seriously considered a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, but as you know, many theaters today aren’t able to project in 1:33, so our choice would’ve been to shoot in 1:85 and then create a black matte atop the 1.85, and we felt that would be too intrusive. Also, Marty and I instinctively felt the visual movement of the film lent itself strongly to widescreen, a format we both love. Did you filter or diffuse your lenses to affect a period look? Richardson: Well, what exactly is a period look? Do you think faces looked softer back then? I’m wondering whether that’s true, or if Clark Gable actually looked relatively sharp in a first-generation print of Gone With the Wind. Certainly, cinematographers did use diffusion [on faces] at that time if appropriate, but they were also working with slower film stocks and, as a consequence, harder lights, which would have extended the apparent clarity of the image. We tend to think that when you go back in time, the ambience grows warmer and diffused, and that is certainly true for some pictures. But for The Aviator, I used very little diffusion on the lenses to affect a period look. |

|

|||

|

next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|