|

||||

|

|

|||

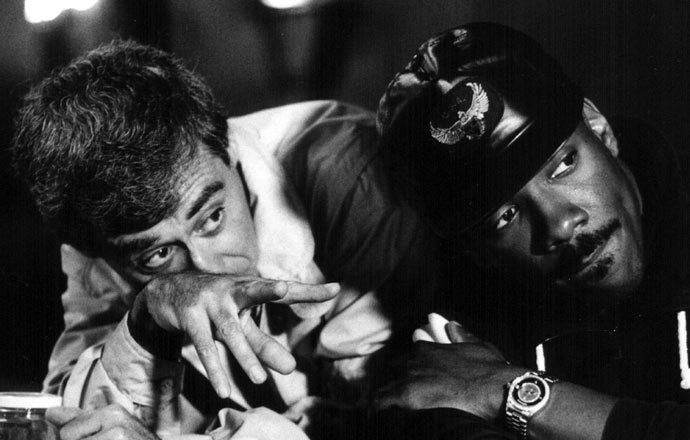

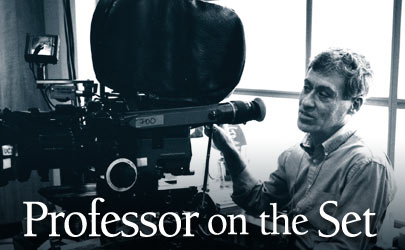

“Now, there are cinematographers who put themselves first, but no great cinematographer puts himself above the script, because that’s always going to be translated through the director and actors. To excel at cinematography, you have to learn to do what Conrad Hall [ASC] was so great at: process all that input in your mental computer and translate it visually. When it’s done right, it’s magic, and Connie was the master of it. The results don’t look like anything else you’ve shot, but they have a familiar creative essence.” Omens’ feature credits include the comedies History of the World: Part I (1981), Coming to America (1988) and Harlem Nights (1989), the latter of which was actor Eddie Murphy’s directorial debut. “Eddie and I had formed a good working relationship while making Coming to America,” says Omens, referring to the fish-out-of-water tale about a dapper African prince seeking true love in Queens, New York. Murphy plays several roles in the film, and some called for elaborate prosthetics (created by makeup artist Rick Baker). “Working with Rick Baker was a great collaboration because the makeup was so good, and because I was very critical about what could stand up in close-ups, angles that would reveal seams and lighting that didn’t look right, and Rick welcomed my input. There was a great dialogue between us, and that’s key to any success on the set. “But the cameraman has to have an eye for detail even with just standard makeup, and one thing I insisted upon with Eddie’s ‘normal’ makeup was that his artist powder him just inside the ears. Good makeup has a smooth tonality, and that inside part of the ear can sometimes be shiny, which can result in a very distracting highlight in profile shots. It’s much more distracting if the actor has dark skin, and there’s nothing you can do about it unless you catch it before you shoot.” The time-saving lighting techniques Omens mastered earlier in his career became vitally important, because “if one needed the usual 20 or 30 minutes of re-lighting to move in from a wide shot to a close-up, Eddie would leave the set, and it could take a considerable amount of time to get him back. But early on, I convinced him I could do it in five minutes — if he just took a seat in place, I could relight and get him back to performing very quickly. It was a matter of building most of his close-up lighting into the master and making just a few small adjustments to get it right. I proved it could work, and Eddie was very happy. He’s a complete professional, and anything I could do to keep things moving was very welcome. I think that’s one reason why he asked me to shoot Harlem Nights.” Set in the 1930s, Harlem Nights features Murphy as the smooth-talking owner of an illegal casino who is trying to simultaneously dodge crooked cops and the Mob. The film features an impressive crew, including production designer Lawrence G. Paull and costume designer Joe I. Tompkins. “Most of the story took place in Harlem in 1938, and more recent movies set in that period tend to look like faded photographs,” notes Omens. “That’s because our visual memory is based on a visual cliché, sepia-toned images we associate with photo albums and old picture books. We searched bookstores, libraries and archives for clues about what Harlem was like during the late 1930s. One of the best sources we found was Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto [by Gilbert Osofsky]. I originally thought we should shoot in black-and-white, but after researching, I decided to make black skin tones the most essential color in the film and use a limited palette. That would set off and highlight the beautiful skin tones of our cast, which was mostly black. I didn’t know what Eddie and Larry Paull and Joe Tompkins would think about this, so I created a color chart to demonstrate my idea. After seeing it, they supported the idea, and it became the basis for the look of the entire picture. In that environment, a few very strong color accents seemed to jump off the screen, but most importantly, the skin tones of the actors dominated each scene. “My only disappointment was that it’s so far the only film Eddie has directed,” he adds. “He just didn’t like to be bogged down by the details of directing. It’s a pity, because he could be a very good director.” In 1992, Omens shot another Murphy vehicle, Boomerang, a romantic comedy in which the actor stars as a womanizing advertising exec who meets his match in his new boss (Robin Givens) and her assistant (Halle Berry). “Reginald Hudlin directed the film, and though we had a good collaboration, I know I was there because of Eddie — he felt comfortable working with me,” says Omens. “That meant a lot to me.” After Boomerang, Omens dedicated himself to full-time teaching at USC. “I suppose I’ve lived a bit of a double life,” he says, noting that he had been serving as a part-time instructor there since 1967. “Some of my crew have joked over the years that I was the ‘professor on the set.’ But teaching has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life; it has taught me more than I would have ever learned on my own. I learn so much from my students, and they keep me energized.” Omens taught at USC full time until 2004, when he was named Professor Emeritus. He recently presented the Conrad W. Hall Chair in Cinematography and Color Timing to Judy Irola, ASC on behalf of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. As president of the ASC, a position he held from 1998-99, Omens ramped up the Society’s educational activities and re-activated the student Heritage Award program, which had lain dormant for many years. He is currently furthering the training of tomorrow’s filmmakers by raising funds to build the ASC Technology and Education Center, which will be located next to the organization’s famed Clubhouse in Hollywood. “I suppose if I have a criticism of my work, it’s that I sometimes served other people more than myself,” he says. “I delivered professional work, but in my mind it was never good enough because I didn’t push to do something beyond what was expected. Some of it is lighting, some of it is camera placement, some of it is overall creative conception. For those reasons, [ASC members] Connie Hall, Gordon Willis, Vittorio Storaro and Owen Roizman are heroes of mine — they dared to try things. I never gave myself the chance to take the risks that great artists have to take. That’s a lesson I tried to pass on to my students: take those risks and never have regrets.” |

|

|||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|