HERO • page 2 • page 3 |

|

Page 2 |

||

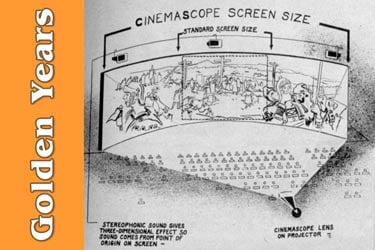

The Chretian system consisted of a "cylindrical" anamorphic attachment to be placed in front of a normal "prime" lens. All three of the lenses were tested. Typical measurements were a change in squeeze ratio across the screen from 1.87:1 in the center of the screen to 2.04:1 halfway to the edge, and 2.37:1 at the very edge. Furthermore, the ratio changed with focus distance, being 2.50:1 at distances greater than 30 feet (9 meters) and shrinking down to 1.80:1 at 5 feet (1.6 meters). When projected at a constant 2:1 squeeze ratio, an actor walking across the screen would become thinner near the edge of the screen, and when photographed in close-up, his face would become fatter. At the same time, Fox asked Bausch & Lomb, an American lens-manufacturing company, to manufacture 250 cylindrical camera attachment lenses as quickly as possible. Although the early Bausch & Lomb attachment lenses were poor and eventually had to be scrapped, those made by Zeiss for Warner's SuperScope system were worse by comparison. In 1954, Panavision founder Robert Gottschalk owned a camera store in Westwood Village, where his customers included many professional photographers and cinematographers. Among his acquaintances was an optical engineer, Walter Wallin, who helped him design a prism-type de-anamorphoser that proved to be far superior to the original CinemaScope cylindrical-type projection lenses. Ironically, Gottschalk and Wallin's lens was based on an even earlier Chretian development. The advantages of the prismatic system of anamorphic attachment lenses were that they were far simpler and less expensive to manufacture, and if the prisms were mounted so that they could be swiveled together, the anamorphic squeeze ratio could be modified. It could easily be set to be 2:1, 1.50:1 and even 1:1 and would remain even and optically true all across the screen. Another advantage was that theaters could build a large reel containing shorts, newsreels and other non-anamorphic films, and an anamorphic film all on the same reel, and could project correct imagery for one or the other at the turn of a small knob - all without stopping the projector. Furthermore, Gottschalk didn't care whether the theater installed four-track stereo sound or not! Within a short time, Gottschalk and a small staff that included Frank Vogelsang, Tak Miyagishima, George Kraemer and Jack Barber produced and delivered some 35,000 prism-type projection lens attachments, until the market became saturated. In 1957, at about the same time that the demand for projection lenses was falling off, MGM asked Gottschalk to develop a set of anamorphic camera lenses with a 1.33:1 squeeze ratio for a film called Raintree County (1957), starring Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift, with which the studio hoped to outdo Gone With the Wind. The system was called Camera 65. It was later refined, changed to a 1.25:1 squeeze ratio and called Ultra Panavision. Another Camera 65 picture was Ben-Hur (1959), the first film shot with Panavision lenses to earn the Academy Award for cinematography. Building upon this success, Panavision developed a system of non-anamorphic lenses for 65mm cameras. They were used on such pictures as Exodus, West Side Story, Lawrence of Arabia and My Fair Lady. Meanwhile, by comparison, the cylindrical-type lenses were proving very difficult and time-consuming to manufacture, and Fox was having terrible problems meeting the needs of all the production companies seeking to shoot films using the CinemaScope system. For all of its faults, CinemaScope was very popular with the public, and neither Fox nor Bausch & Lomb could cope with the demand for lenses. The time came when MGM and other companies, no longer wanting to be reliant upon Fox for CinemaScope camera lenses, approached Gottschalk and asked if he could supply 35mm anamorphic camera lenses. Gottschalk had supplied high-quality lenses to many 70mm productions and had worked with many top Hollywood cinematographers, and he knew the cameramen were unhappy about "anamorphic mumps," Cinema-Scope's tendency to make an artist's face look fat in close-up. When Gottschalk came to design his anamorphic camera lenses, he remembered that two prisms in combination could be used to control the anamorphic ratio. He remembered, too, that optometrists had in their drawers of test lenses a special device used to test for astigmatism; it consisted of two thin, circular prisms that could be contra-rotated relative to one another to increase or decrease astigmatism. Page

2

|

||