|

||||||

|

|

|||||

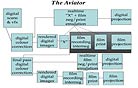

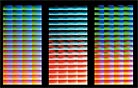

Analog film projectors are set up to output 16 foot-lamberts of luminance with an open gate. Put film in the gate and only 11 to 14 foot-lamberts hit the screen. Fourteen is the target for digital cinema projectors as well. (And now for the rhetorical question: are these luminance levels maintained in theaters?) You can go much brighter with analog projectors, and the perceived colorfulness would increase, but flicker would be introduced, especially in the peripheral vision. Flicker is not so much a problem with digital projection because there is no shutter. However, lamp size and heat management are the roadblocks to increased brightness. “With the xenon light source,” adds Kennel, “you can actually push color gamut out beyond TV, beyond Rec 709, and out beyond most of the colors in film, except for the really deep, dark cyans.” An interesting example of this constraint can be seen in The Ring (AC Apr. ’02). Projected on film, cinematographer Bojan Bazelli’s overall cyan cast to the imagery comes through, but when viewed on a Rec 709 or Rec 601 RGB display that lacks most cyan capability, that cyan tint shifts to a bluish-gray because shades of cyan aren’t reproduced well, if at all, in those RGB color gamuts (see diagram). DLP projection also offers onboard color correction, but loading a LUT for a particular film into every theater’s projector isn’t feasible. Instead, DLP projectors function within preloaded color profiles. Typical RGB has three primary colors, and its corresponding color profile for the DLP digital projector is known as P3. Pixar’s animated Toy Story 2 (1999) used a P3 color profile for its digital cinema master. But other colors can be designated as primaries to expand the mix and match palette, as Texas Instruments has done with the P7 system – red, green, blue, magenta, cyan, yellow and white. “We were trying to color correct a scene that had red geraniums, green grass and warm skin tones,” remembers Cowan. “When we balanced out the green grass and red geraniums so they looked natural, the skin tone went dead. When we balanced the skin tones, the green grass and red geraniums looked fluorescent, so we had a fundamental color-balance problem. Skin tones end up in the yellow area a lot. Yellow should be a combination of red plus green, but in order to get bright enough yellows, we had to crank the red and green brightness too high. What we did in the P7 world was reduce the target luminance of the red and the green but left the target luminance of yellow high. In fact in P7, we can get very bright yellows without getting very bright greens or reds associated with it.” Throw in some inverse gamma 2.6 to get good quantization to go with the P7 profile (it’s P7v2 now), and you’re ready for digital projection. Well, not quite. The goal of DCI was to establish digital cinema distribution parameters and out of that came the DCDM, the Digital Cinema Distribution Master, which stipulates a conversion of the materials to wide-gamut CIE XYZ color space and the use of the MXF (Material eXchange Format) file system and JPEG 2000 codec. JPEG 2000 uses wavelet transform compression and offers the capability of compressing a 4K file and extracting only the 2K image file out of that. The future of projection could be in lasers. Levinson has followed the development of a laser projector by a company in Kansas City. He’s under a non-disclosure agreement and can’t say much about the projector, but the way his face lights up at the mention of it says it all. Lasers can produce true black (because when they’re off, they’re off without slow light decay) and will widen the color gamut beyond all current display technologies. “If these lasers can be made to work, we would be entering into an uncharted realm,” admits Clark. “It moves that color space into another dimension.” For now, questions about the technology remain: Is it feasible for commercialization? What happens to your hair when you stand up into the laser beam? The ASC Technology Committee is well aware of the possibility that any standards to come out of the current workflows actually may undermine rather than assist image quality and marginalize those best equipped to manage the image — cinematographers. For this reason, they are serving as a sort of forest ranger in the digital frontier. In doing so, Clark has created an ideal workflow guide that includes all the tools needed to maintain image integrity throughout the hybrid film/digital process (see diagram). Rather than being equipment-centered and rigid, the workflow specifies best-practice recommendations, allowing for inevitable technological innovations. “We’re stepping in with a proposal of what needs to happen,” he indicates. “We’re not only assessing currently available workflow management tools and applications, but also identifying a set of functions that need to be integral to these workflow solutions in order to maximize both creative potential and cost efficiency.” Key to this workflow is the integration of “look management” that begins on the set. “This optimized workflow incorporates the provision for a look management function that can be utilized at every stage of the filmmaking process, from previsualization through to final color correction, with tool sets that are designed for the cinematographer,” he says. “This reinforces the importance of the cinematographer’s traditional role in the creative process, which not only includes setting the look in terms of the image capture but also managing that look all the way through final color correction and digital mastering to the distribution of a theatrical release on film, DCDM, DVD, HDTV, SDTV, etc. “Unfortunately,” he continues, “most currently deployed color-grading application tool sets are designed without the cinematographer in mind. The hybrid digital/film workflow has evolved as an ad hoc patchwork of tool sets, fixes and workarounds that people come up with to get the work completed within what has become an outmoded workflow process that separates postproduction from principal photography. Only recently have people begun thinking of the hybrid digital/film imaging workflow as a holistically integrated design that blurs the prior, distinct territorial boundaries between production and post. This new ‘nonlinear’ workflow can and should provide the cinematographer with flexible access to images throughout the imaging chain, enabling him or her greater management control of the look so that final color grading is where the finishing touches are applied, and not the place where the look is ‘discovered.’” As of now, “this new look-management component is embryonic at best,” he says, “but it needs to be made a focus by the manufacturing community so that they understand that this is critical. They need to design their solutions with the new nonlinear workflow in mind and create products that provide the appropriate functionality.” Systems such as the Kodak’s Look Management System, Filmlight’s Truelight system, 3CP’s Gamma & Density and Iridas’ SpeedGrade provide on-set computer color correction and look-management functions that are handled in different ways in the dailies lab, depending on the product. Some create metadata and some don’t. Once some form of consensus is formed, metadata will include important color decisions in the image files. Sony Pictures is running tests to see if Gamma & Density, an on-set HD dailies color correction tool, can carry metadata through a DI pipeline on the remake of Fun with Dick and Jane, shot by Jerzy Zielinski, ASC. In using on-set look-management tools, a certain balance must be struck so that you aren’t slowing your production process down in order to gain on the post side of things. It’s like robbing Peter to pay Paul, as the old adage goes. To avoid such a situation during the production of Closer (AC Dec. ’04), Stephen Goldblatt, ASC, BSC employed Kodak’s LMS only selectively. But by using the LMS on selected scenes, Goldblatt was able to convey to director Mike Nichols what the intended look would be, even on HD dailies. A future possibility would be to bypass HD dailies altogether and have projected 2K data dailies that avoid a conversion to video color space. This possibility could allow the cinematographer to assess more of what is on the negative, and at 2K resolution, the image files could be used for much more than just dailies. Another possibility for data dailies could be a type of “digital match clip” for visual-effects work, in other words, pregraded material. Notes visual-effects supervisor Richard Edlund, ASC, “In our digital age, and especially in the event that the cinematographer has the luxury of using a DI, it is important to visual-effects artisans to receive a digital version of the photochemical match clip of any background plates, so that any added bluescreen or other CG elements can be balanced to look natural within the sequence. Because we are seeing a move away from the tradition of making film prints for dailies screenings, photochemical film match clips have become more difficult or impossible to get." To carry color choices through the workflow from production to post, the Digital Intermediate subcommittee has been developing a Color Decision List (CDL) that functions like an editor’s Edit Decision List, or EDL, but is for color-grading choices. The CDL proposal, led by Levinson and Pines (who wrote the CDL white paper with David Reisner of Synthesis), has manufacturers jumping onboard. Cinematographers should be paid for their postproduction time and are more likely to be paid if the value proposition of their contribution is realized by producers. But think about it: the CDL would carry the cinematographer’s choices through the workflow and increase efficiency. And the cinematographer no longer would have to hover over monitors or the colorist’s shoulders the entire time, thereby reducing his or her time and cost. And speaking of EDLs, the ASC and the American Cinema Editors union (ACE) have begun cooperating in an effort to bring color-corrected images of a higher quality, such as eventual 2K data dailies, into their nonlinear editing systems. Traditionally, editors cut low-resolution, uncorrected or limited-correction dailies and often make cuts based on trying to match or disguise unbalanced images viewed on uncalibrated monitors. When the cinematographer does a final color grade, some of the edits no longer work. Plus, after looking at those inferior images for months at a time, directors tend to fall in love with those looks, incorrect though they may be. Where does this all lead? To the ASC Technology and Education Center, scheduled to break ground next to the ASC Clubhouse this summer. In 1937, the year the Society moved into that storied Clubhouse, the ASC was positioned in the middle of orange groves. Sixty-seven years later, it is positioned in the middle of the digital-imaging evolution. “The center will give us a place to be able to do our own experimentation, evaluation and analysis of digital workflow technologies in a much more effective way,” proclaims Clark. “The center also will facilitate our ability to collaborate more efficiently with both the AMPAS Science and Technology Council and the University of Southern California’s Entertainment Technology Center on important projects. We’ll be the only industry organization of professional filmmakers that has essential resources to evaluate all aspects of the hybrid motion-imaging chain. The center will house the only fully calibrated, standards-based, reference screening room. Our work will reinforce the value proposition for the cinematographer’s role in managing the look within the new hybrid imaging workflow. As a consequence, we will generate greater awareness and respect for what cinematographers do and cement the importance of the ASC’s leadership role. We’re the neutral ground that is the interface with the user base.” Where once was a frontier, an ASC technological proving ground will soon exist. Manufacturers will be welcome to use the facility during research and development of new tools and technologies, he adds. The aim of the ASC Technology Committee is to fully understand the convergence of film and digital imaging technologies within the new hybrid motion-imaging workflow. This historically unprecedented convergence demands more efficient workflow practices, and it is the ASC’s objective to influence the development of technologies within this workflow that will enable cinematographers and their collaborators to exploit the creative potential for enhanced image control with a new breed of effective, cost-efficient look-management tools. These new tools, if engineered properly, will reinforce the cinematographer’s role as both a creator and guardian of the artistry of the cinematographic image, a role that has been a creative cornerstone of the collaborative filmmaking process since its inception. Jump to: “The Color-Space Conundrum, Part 1”

|

|

|||||

|

<< previous || next >> |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||